BH SYNERGY - CBD ANIMALS WHITE PAPER

MARKETS REPORTS:

Animal Health Europe Annual Report 2017

Animal Health USA Industry Report AHI 2018

PET OWNERS TREATING SICK DOGS WITH CBD OIL

There are dozens of cannabinoids, but CBD is one of the most abundant and well-studied cannabinoids. According to scientific research, CBD can have a great number of benefits for humans and dogs.

More and more animal lovers are using CBD products to manage their pets’ health conditions. Recently, research and anecdotal evidence have suggested that there are many benefits of CBD oil for dogs, in particular.

Let’s back up for a second: what is CBD? Cannabidiol, which is known as CBD, is a cannabinoid. Cannabinoids are the ‘active ingredients’ found in hemp and cannabis plants. These cannabinoids affect many parts of our bodies, from the brain, to the skin, to other major organs. It can affect your mood, thinking skills, and bodily functions.

There are dozens of cannabinoids, but CBD is one of the most abundant and well-studied cannabinoids. According to scientific research, CBD can have a great number of benefits for humans and dogs alike.

Just as humans can be affected by the benefits of CBD oil, so can dogs!

Every pet owner needs to know about the benefits of CBD oil for dogs. If you’re interested in learning more, read on.

What are the benefits of CBD oil for dogs?

Over the past few years, a number of scientific studies have looked at the benefits of CBD. As we speak, more research is being done into the benefits of CBD oil for dogs. For now, there are a number of confirmed benefits.

A 2018 veterinarian survey looked at 2130 US-based veterinarians and their experience with giving CBD to animals. The results showed that veterinarians found CBD oil to be very effective in helping reduce seizures, chronic pain, and anxiety. Many studies confirm this.

Here’s what the science says about the benefits of CBD oil for dogs:

CBD oil can help dogs with chronic pain. A 2018 study conducted at Cornell University looked at dogs with osteoarthritis. The study found that CBD oil soothed their pain and increased their activity levels.

CBD oil can soothe your dog’s skin. A 2012 study looked at how CBD affects dogs with atopic dermatitis, an inflammatory skin condition. The results indicated that CBD greatly improved skin conditions.

CBD oil reduces seizures in epileptic dogs. A 2017 study found that the dogs who had CBD oil had fewer seizures than those who didn’t. Given how CBD oil is a proven treatment for humans who have seizures, this is unsurprising.

While there is a lot of anecdotal evidence that CBD oil improves anxiety, more information is needed, as this 2018 paper points out. We know that CBD oil can benefit dogs, but plenty more research needs to be done before we understand all the benefits of CBD.

How do I give my dog CBD oil?

If you’re interested in using CBD oil for your dog, there are a few things you need to know.

Firstly, it’s important to find high-quality CBD oil. When it comes to your furry friend, their health is worth the investment. Unfortunately, there are some companies out there that create low-quality CBD oil. Some companies have even created oil claiming that it contains CBD when it does not.

Luckily, there are plenty of great CBD products for your pets - you just need to know where to find them. Check out DogDreamCBD to find the best CBD products for your dog.

Secondly, the dosage is important. Many people don’t know how much CBD to give their dogs. The amount of oil you give them depends on their breed, size, and condition, as well as the strength of the oil. Often, the product will include instructions on dosing. Bare in mind that CBD can come in the form of oil droplets and CBD-infused dog treats.

It’s always advisable to talk to a veterinarian before giving your dog any supplements, as they’ll give you specific instructions on the dosage. You can also take a look at our dosage chart to find out how much CBD your dog needs.

Is it safe to give my dog CBD oil?

As a dog owner, you’re understandably concerned about whether it’s safe to give your furry family member CBD oil.

CBD oil is safe for dogs. While studies have found cannabis itself can be toxic to dogs, CBD alone is perfectly safe.

There are a few possible side-effects of CBD oil on dogs, although none are life-threatening. The 2018 survey of veterinarians mentioned above noted that the only common side-effect of CBD oil was that pets often became sleepy after ingesting it.

Many dog owners wonder: can CBD get my dog high? In short, no. CBD isn’t intoxicating, but another cannabinoid - THC - is. In other words, THC makes you high, not CBD. If your pet has pure CBD oil, they shouldn’t get high at all.

There are multiple benefits of CBD oil for dogs, and scientists are bound to discover many more in the years to come. If you want to give your dog CBD oil, it’s important to do your research and chat to a veterinarian beforehand.

RESEARCH

US Veterinarians' Knowledge, Experience, and Perception Regarding the Use of Cannabidiol for Canine Medical Conditions

Due to the myriad of laws concerning cannabis, there is little empirical research regarding the veterinary use of cannabidiol (CBD). This study used the Veterinary Information Network (VIN) to gauge US veterinarians' knowledge level, views and experiences related to the use of cannabinoids in the medical treatment of dogs. Participants (n = 2130) completed an anonymous, online survey. Results were analyzed based on legal status of recreational marijuana in the participants' state of practice, and year of graduation from veterinary school. Participants felt comfortable in their knowledge of the differences between Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and marijuana, as well as the toxic effects of marijuana in dogs. Most veterinarians (61.5%) felt comfortable discussing the use of CBD with their colleagues, but only 45.5% felt comfortable discussing this topic with clients. No differences were found based on state of practice, but recent graduates were less comfortable discussing the topic. Veterinarians and clients in states with legalized recreational marijuana were more likely to talk about the use of CBD products to treat canine ailments than those in other states. Overall, CBD was most frequently discussed as a potential treatment for pain management, anxiety and seizures. Veterinarians practicing in states with legalized recreational marijuana were more likely to advise their clients and recommend the use of CBD, while there was no difference in the likelihood of prescribing CBD products. Recent veterinary graduates were less likely to recommend or prescribe CBD. The most commonly used CBD formulations were oil/extract and edibles. These were most helpful in providing analgesia for chronic and acute pain, relieving anxiety and decreasing seizure frequency/severity. The most commonly reported side-effect was sedation. Participants felt their state veterinary associations and veterinary boards did not provide sufficient guidance for them to practice within applicable laws. Recent graduates and those practicing in states with legalized recreational marijuana were more likely to agree that research regarding the use of CBD in dogs is needed. These same groups also felt that marijuana and CBD should not remain classified as Schedule I drugs. Most participants agreed that both marijuana and CBD products offer benefits for humans and expressed support for use of CBD products for animals.

Introduction

Cannabis is one of the earliest cultivated crops, grown in Taiwan for fiber starting about 10,000 years ago (1). The Emperor Shen-Nung, a pharmacologist, wrote a book on treatment methods in 2737 BCE that included the medical benefits of cannabis and recommended it for many ailments, including constipation, gout, rheumatism, and absent-mindedness (2). Cannabis plants can be genetically classified as either hemp or marijuana, based on the concentration of (-)-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and other cannabinoids they contain (3). Marijuana typically refers to plants with high concentrations of THC, the psychotropic drug used for medicinal or recreational purposes. In contrast, hemp is typically cultivated for use in personal care products, nutritional supplements, and fabrics. It contains higher amounts of CBD, which does not have psychotropic properties. The rules and regulations for CBD and marijuana are different with each having separate statutory definitions.

Recently, the US senate debated the legalization of industrial hemp, with the introduction of the Hemp Farming Act of 2018, aimed at lifting the ban on hemp as an agricultural commodity. Incorporated into the larger 2018 Farm Bill the hemp farming act was passed. The Hemp Farming Act provides for the removal of industrial hemp from Schedule I of the Controlled Substance Act (CSA). This removal would explicitly legalize the cultivation, processing and sale of all hemp-derived products, including CBD (4). The final stages of this legalization process are yet to develop. In September, 2018 the U.S. Department of Justice and the Drug Enforcement Agency announced that Epidiolex (newly approved CBD containing anti-seizure medication) was placed in Schedule V. The DEA signaled that this approval only applied to Epidiolex and not all CBD products (5).

As such, the legal status of CBD remains confusing. According to the Drug Enforcement Agency, Schedule V drugs, substances, or chemicals are defined as drugs with lower potential for abuse than Schedule IV and consist of preparations containing limited quantities of certain narcotics. Schedule V drugs are generally used for antidiarrheal, antitussive, and analgesic purposes (6).

The confusion around legal status of cannabis has made it challenging to study its effects, yet the demand for recreational and medical cannabis continues to grow. Sales of legal recreational and medical cannabis in the United States in 2017 resulted in $5.8–$6.6 billion revenue, and by 2022, legal cannabis revenue in the U.S. market is projected to reach $23.4 billion (7).

Against this backdrop, research remains minimal. Those wishing to study the effects of cannabis or cannabinoids must navigate a challenging process that may involve the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Food and Drug Administration, Drug Enforcement Administration, offices or departments in their state's government, state boards, their home institution, and potential funders (8). There have been a handful of controlled clinical trials conducted with cannabinoids, reporting positive effects on pain, nausea, vomiting, inflammation, cancer, asthma, glaucoma, spinal cord injury, epilepsy, hypertension, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, or loss of appetite (9–11). In late June 2018, the FDA approved Epidiolex, the nation's first drug derived from marijuana, for the treatment of seizures associated with two rare and severe forms of epilepsy in humans (12).

Research on animals is equally challenging, with few researchers studying cannabis in animal patients without explicit FDA and DEA approval, but in a manner they contend complies with federal and state law. A researcher from Colorado State University recently reported findings from a small pilot study involving 16 dogs. She found that 89 percent of epileptic dogs had fewer seizures when taking the chicken-flavored CBD oil, as compared to about 20 percent that had were on a placebo (13). Another project, conducted at Cornell University, included a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind crossover study that appeared to show that dogs treated with CBD oil have a clinically significant reduction in pain and an increase in activity (14). Given its growing popularity, it is important to assess small animal veterinary practitioners' experiences with CBD products for dogs. This current study was designed to gauge US veterinarians' knowledge level, views and experiences related to use of cannabinoids in the medical treatment of dogs. This study was not designed to study perceptions, views, or experiences related to the use of marijuana products with high levels of THC in dogs. The authors' perception is that there is much more interest in the public for using CBD products in dogs, possibly due to concerns over THC toxicity.

Method

An anonymous online survey was created, in collaboration with VIN (Veterinary Information Network–an online veterinary community), to evaluate veterinarians' views regarding marijuana and CBD/hemp products. The survey was created and tested for usability by researchers at Colorado State University. After the survey was created, one of the authors of this paper (MR) set up online distribution and arranged for a small sample of VIN members to pilot test the survey for appropriate branching and question flow, ambiguity, and potentially missing or inappropriate response options. Their feedback was analyzed, and incorporated into the final version of the survey. A link to the survey was distributed via an email invitation to all VIN members (n~34,000), and access was made available from April 27, 2018- May 16, 2018. A follow-up message was sent 2 weeks after the initial invitation. Only data from respondents who stated they currently treat dogs in clinical practice were included in the study. The study was categorized as exempt by Colorado State University's Institutional Review Board. Because this was an anonymous survey, written informed consent was not required. An introductory statement explained the study and indicated to potential participants that consent was implied by completing the survey.

The survey was administered directly via the VIN data collection portal, and branching logic was used to display only questions relevant to each participant. The first question was a screening tool to ensure respondents were clinical veterinarians practicing in the US. Veterinarians who self-identified as not in a US clinical practice (n = 26) or did not treat dogs (n = 52) were eliminated from further analysis. The body of the survey consisted primarily of short questions, for which participants were able to select one or more specific options to represent their experiences and perceptions regarding hemp/CBD products. Free-text boxes were provided for participants to enter brief alternative answers when none of the listed options applied to them. A final question at the end of the survey allowed for free-text entry of any comments participants chose to make about hemp/CBD products.

Results

A total of 2,208 responses were received, 78 of which were eliminated as per above, leaving a sample size of 2,130. Not all survey questions received responses; therefore, the number responding to that particular question is indicated for each question in the text and tables. Respondents practicing in each state in the US participated, with the largest percentages coming from California (341, 16%), Texas (142, 6.7%), Florida (113, 5.3%), New York (96, 4.5%), and Colorado (92, 4.3%). The number of respondents who work in a state in which recreational marijuana was legal at the time of the survey (AK, CA, CO, DC, ME, MA, NV, OR, VM, WA) was 759 (35.6%) leaving 1,371 respondents (64.4%) working in states that had not legalized recreational marijuana as of May, 2018. Respondents were asked to indicate the year in which they graduated veterinary school. The graduation years were classified into four cohorts: 1989 or earlier (448, 21.1%), 1990–1999 (473, 22.3%), 2000–2009 (606, 28.6%), and 2010 or later (595, 28.0%).

Knowledge Questions

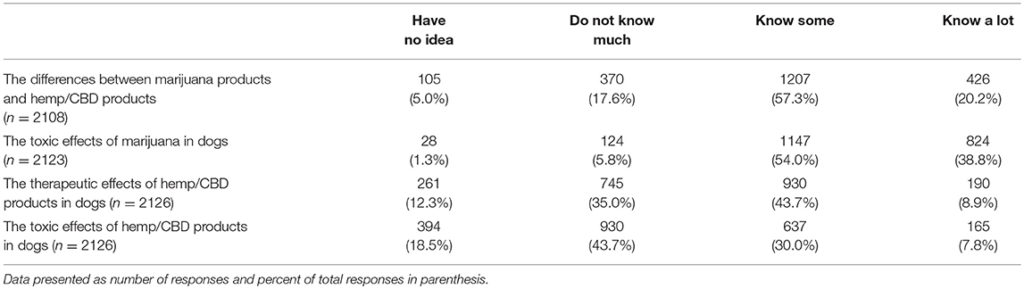

Respondents were asked to indicate their knowledge level, using a 4 point Likert scale from 1 = “have no idea” to 4 = “know a lot,” in response to questions about marijuana and/or CBD products. The first question enquired about their knowledge level regarding the differences between marijuana and CBD products (n = 2,108). The largest number (1,207, 57.3%) reported “know some” followed by “know a lot” (426, 20.2%). When asked about the toxic effects of marijuana in dogs (n = 2,123), the majority reported “knowing some” (1,147, 54.0%), followed by “know a lot” (824, 38.8%). Respondents were less knowledgeable about the therapeutic effects of CBD products in dogs (n = 2,126); 930 (43.7%) reported “knowing some” and 745 (35.0%) reported “not knowing much.” Similarly, they were less knowledgeable about the toxic effects of CBD products in dogs (n = 2,126), in which 637 (30.0%) reported “knowing some” and 930 (43.7%) reported “not knowing much.” (Table 1).

TABLE 1

Table 1. Veterinarians self-reported knowledge level regarding marijuana and hemp/CBD products in dogs.

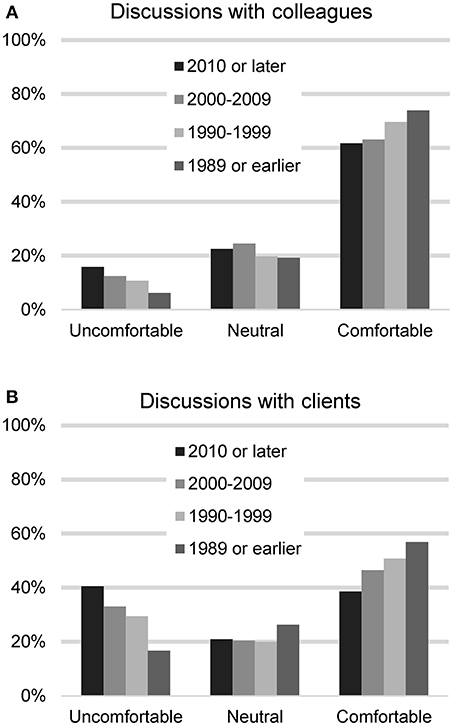

The respondents were asked next how comfortable they feel talking to veterinary colleagues about CBD treatment for dogs (n = 2,127). Most felt comfortable (1,309, 61.5%), with 231 (10.9%) reporting feeling uncomfortable, 432 (20.3%) neutral, and 155 (7.3%) indicating they have not encountered the situation. When asked about their comfort level talking with clients, they were less comfortable: 967 (45.4%) reported feeling comfortable and 641 (29.9%) felt uncomfortable, 443 (20.8%) neutral, and 85 (4.0%) indicated they have not encountered the situation. A chi square test was used to assess differences in comfort level based on graduation year and legal status of recreational marijuana in the respondents' state of residence. For these analyses, those who had not encountered the situation were removed. No differences were found based on legal status of marijuana in state of practice, but differences were found based on graduation date. Recent veterinary graduates were less comfortable talking to colleagues (chi square 29.71, p < 0.001) as well as clients (chi square 69.22, p < 0.001) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

Figure 1. Participants' reported level of comfort in discussing CBD/hemp with colleagues (A) and with clients (B), based on year of graduation from veterinary school.

Frequency of CBD-Related Consultations

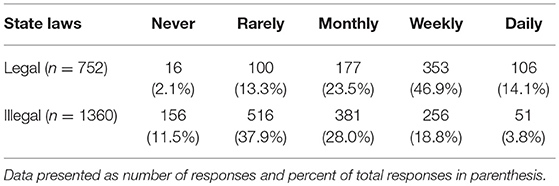

Veterinarians (n = 2,112) were asked how often their clients enquired about CBD products and the most common response was rarely (616, 29.2%), followed by weekly (609, 28.8%), monthly (558, 26.4%), never (172, 8.1%), and daily (157, 7.4%). These responses were significantly different based on respondents' states' marijuana laws (Table 2). Clients visiting veterinarians who work in states that have legalized recreational marijuana were more likely ask about CBD for their pets (chi square 358.90, p < 0.001).

TABLE 2

Table 2. Reported frequency of clients seeking information about CBD for pets, based on legal status of recreational marijuana in state of practice.

Participants (n = 2,128) were also asked to quantify how often they initiate discussions with clients about CBD products. The majority reported never (1,398, 65.7%), followed by rarely (413, 19.4%), weekly (140, 6.6%), monthly (132, 6.2%), and daily (45, 2.1%).

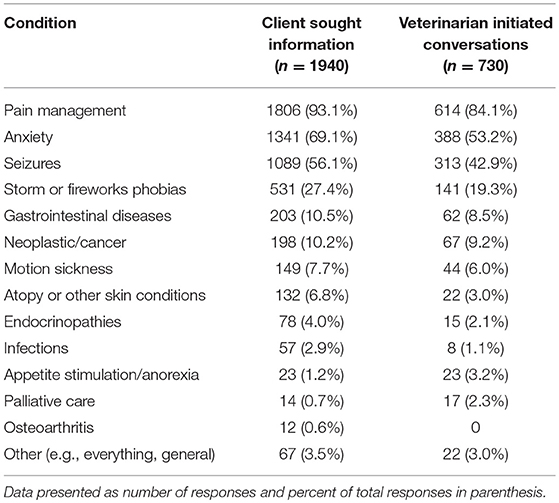

Conditions for Which CBD Was Discussed

Respondents who reported client-initiated conversations about CBD products (n = 1,940) were next asked to identify the specific conditions or diseases for which clients were seeking information. More than one response was possible, and the most common topics were pain management, anxiety, seizures, and storm/fireworks phobias. Respondents (n = 730) who reported initiating conversations with clients about CBD products were also asked to identify the specific conditions or diseases for which CBD products were discussed. Multiple selections were possible, and the most commonly discussed topics were pain management, anxiety, seizures, and storm/fireworks phobias (Table 3).

TABLE 3

Table 3. Common diseases/conditions for which clients sought information and for which veterinarians initiated conversations about CBD.

Client Communication Regarding CBD

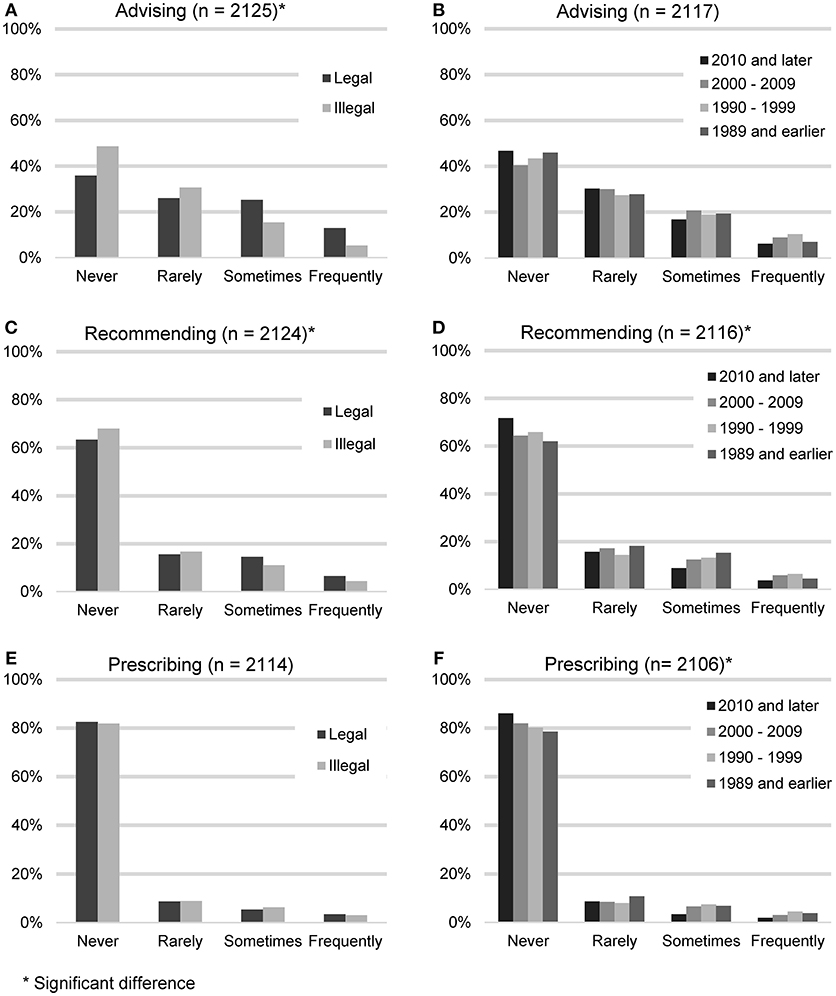

In order to gauge the degree with which veterinarians endorse the use of CBD products, participants were asked to quantify the frequency with which they advise clients about CBD products, recommend CBD products, or prescribe CBD products. These results were then analyzed based on the legal status of recreational marijuana in respondents' state of practice (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2

Figure 2. Reported frequency of advising about, recommending, and prescribing CBD products, based on the legal status of recreational marijuana in participants' state of practice (A,C,E) and participants' year of graduation (B,D,F).

Advising clients about CBD products (n = 2,125) was considered the lowest level of endorsement. The largest number of participants reported never (938, 44.1%) or rarely (615, 28.9%) advising their clients about CBD products. A smaller number reported sometimes (401, 18.9%), or frequently (171, 8.0%). When asked for all the reasons why they did not advise clients about CBD products (n = 938), the most common answer was that they don't feel knowledgeable enough (639, 68.1%), followed by the field needs more research (560, 59.57%), it is illegal (458, 48.8%), concerns about toxicity (185, 19.7%) and do not think clients would be receptive (35, 3.7%). “Other” reasons included concerns about product consistency and purity or the fact that they had not been asked.

Recommending CBD products constituted the next level of endorsement. Participants were asked how often they recommend CBD products (n = 2,124). The majority reported never (1,409, 66.3%) or rarely (346, 16.3%). A minority reported sometimes (260, 12.2%), or frequently (109, 5.1%). When asked for all the reasons why they did not recommend CBD products (n = 1,409), the most common answer was that the field needs more research (912, 64.7%), followed by not feeling knowledgeable enough (888, 63.0%), it is illegal (751, 53.3%), concerns about toxicity (301, 21.4%) and do not think clients would be receptive (45, 3.2%). The most common “Other” reasons included concerns about product consistency and purity and the feeling that other options with better research exist.

Lastly, participating veterinarians were asked how often they prescribe CBD products (n = 2,130). The majority reported never (1,735, 82.1%) or rarely (187, 8.8%). A minority reported sometimes (125, 5.9%), or frequently (67, 3.2%). When asked for all the reasons why they did not prescribe CBD products (n = 1,735), the most common answer was that it is illegal (1,003, 57.8%), followed by the field needs more research (997, 57.5%), don't feel knowledgeable enough (967, 55.7%), concerns about toxicity (325, 18.7%), and do not think clients would be receptive (49, 2.8%). “Other” reasons included the fact that it can be bought over the counter and the lack of product consistency and purity.

Participants who reported living in states with legalized recreational marijuana were more likely to advise clients about CBD products (chi square 81.64, p < 0.001), and recommend CBD products (chi square 11.04, p < 0.012), but were not statistically more likely to prescribe CBD products (chi square 1.07, p = 0.784). Veterinarians in earlier graduating classes were more likely to recommend CBD products (chi square 20.58, p < 0.015), and prescribe CBD products (chi square 20.24, p = 0.016), but not to advise clients about CBD products (chi square 13.75, p = 0.132).

Clinical Experience with CBD Products

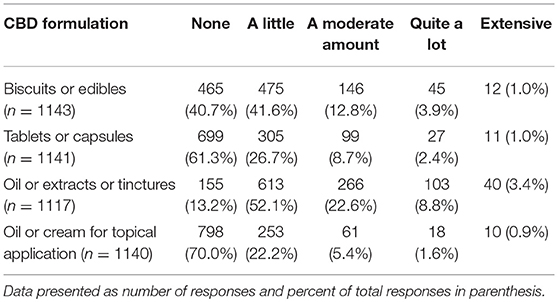

Participants were asked if they have had any clinical experience with CBD products in dogs. This could include direct observation or client reports (n = 2,130). Slightly more than half reported yes (1,194, 56.1%) and 936 (43.9%) said no. Participants who indicated they had clinical experience with CBD were asked a series of questions related to their experience with specific forms of CBD as well as perceived benefits and side effects. The forms of CBD that participants were asked about included biscuits or edibles, tablets or capsules, CBD oil or extracts or tinctures, and oil or cream for topical application. Among these, participants reported the most familiarity with liquid (oil extracts or tinctures) and edible (biscuits/edibles) formulations of CBD (Table 4).

TABLE 4

Table 4. Veterinarians' clinical experience with CBD products in dog.

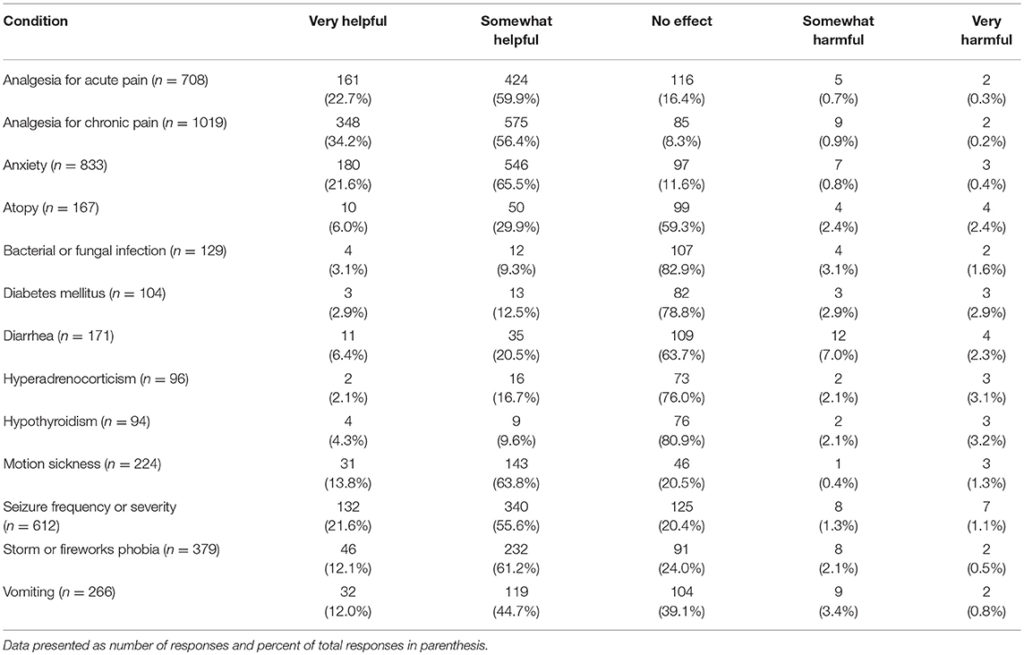

Several potential uses of CBD products were listed and participants were asked to indicate if, in their observations or client reports, CBD products had had a harmful effect, no effect or positive/helpful on each of them. Those who responded NA (not observed/not applicable) were removed from analysis. The areas in which veterinarians reported observing (either first-hand or via client reports) the most positive effects included: analgesia for chronic and acute pain, anxiety, and seizure frequency or severity (Table 5).

TABLE 5

Table 5. Perceived impact of CBD products for common canine medical conditions, listed alphabetically.

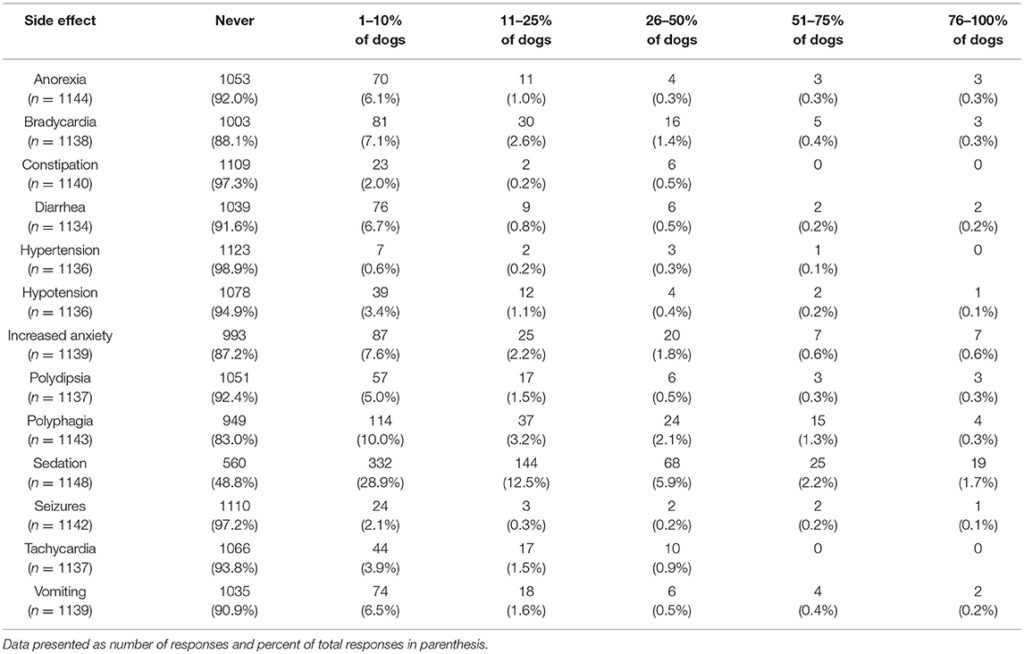

Participants were also asked about witnessed or reported side effects, with the most common side effect being sedation. This was reported by 28.9% of participants to occur in 1–10% of dogs. The percent of participants who reported sedation as a side effect in 11–25% of dogs was 12.5%. The next most common side effect was polyphagia, reported by 10.0% of participants to occur in 1–10% of dogs. With the exception of sedation, all other potential side effects were reported by over 80% of participants as never occurring (Table 6).

TABLE 6

Table 6. Perceived side effects of CBD products for common canine medical conditions.

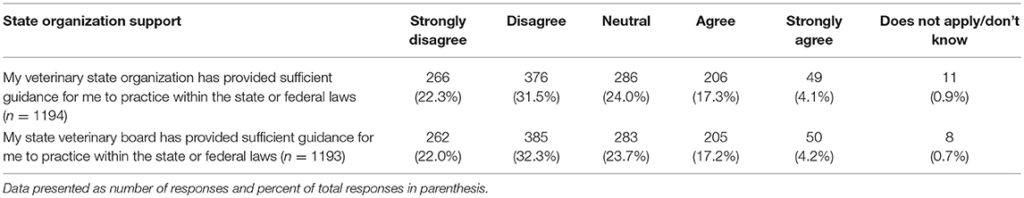

Legal/Ethical Issues and Research Regarding CBD/Marijuana

The last series of questions asked participants about their views on a variety of topics related to CBD and marijuana. Two of these questions referred to guidance on the topic offered through state organizations. For both veterinary state organizations and state veterinary boards, few participants reported feeling that these entities provided sufficient guidance regarding the use of CBD/marijuana in animals for them to practice within the state or federal law. These questions pertaining to veterinary state organizations and state veterinary boards were analyzed to determine if there were any significant differences in responses based on year of graduation or the legal status of recreational marijuana in the state in which respondents' practice veterinary medicine. A significant difference based on year of graduation was found for participants' views of the guidance offered by their veterinary state organization (chi square 30.18, p = 0.011), whereby those who graduated more recently report higher agreement levels. Similarly, those practicing in states with legal recreational marijuana reported higher agreement with the statement that their veterinary state organization provides sufficient guidance (chi square 11.16, p = 0.0480). When asked about their state veterinary board guidance, there was a difference in perception based on year of graduation, with more recent graduates reporting higher agreement levels (chi square 30.04, p = 0.012). No differences were found based on legal status of marijuana in state of practice (Table 7).

TABLE 7

Table 7. Perception of state organizations' provision of sufficient guidance regarding the use of CBD/marijuana in animals to practice within the state or federal laws.

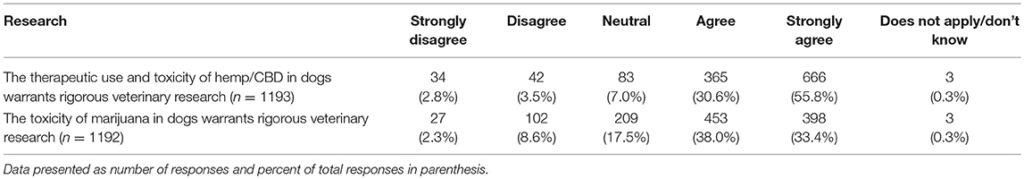

The next set of questions included two questions about the perceived need for additional research, and six questions assessing views of legal status of CBD and marijuana for humans and animals. The results of these questions are summarized in Tables 8, 9. Differences in responses based on the legal status of recreational marijuana in the participants' state as well as date of graduation were assessed with chi square tests and significant differences noted. When asked about the need for additional research about the therapeutic use and toxicity of hemp/CBD in dogs, whose who graduated more recently (chi square 46.61, p < 0.001) as well as those practicing in states with legal marijuana (chi square 28.43, p < 0.001) were more likely to agree that more research is needed. There were no differences between groups for the question related to additional research on the toxicity of marijuana in dogs.

TABLE 8

Table 8. Participants' views regarding the need for hemp/CBD/marijuana research.

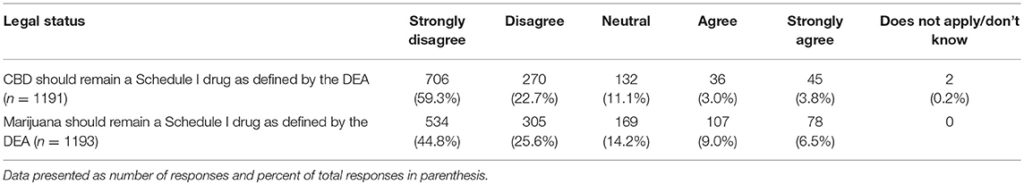

TABLE 9

Table 9. Participants' views regarding legal status of hemp/CBD/marijuana as Schedule 1 drugs.

When asked if CBD should remain a Schedule I drug as defined by the DEA, those who graduated more recently report lower agreement levels (chi square 31.26, p = 0.008) as did those in states that had legalized marijuana (chi square 25.47, p < 0.001). This same pattern was observed for the question on whether marijuana should remain a Schedule I drug as defined by the DEA (graduation year: chi square 47.21, p < 0.001; legalized marijuana status: chi square 27.12, p < 0.001) (Tables 8, 9).

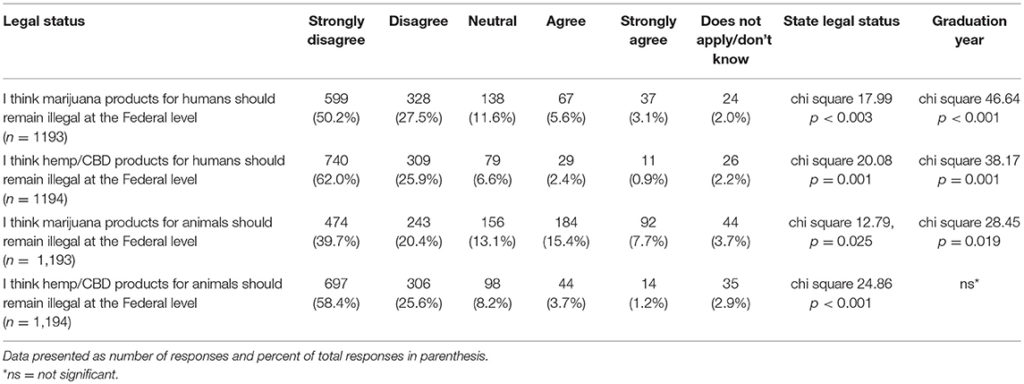

Participants were asked to indicate their agreement level with several statements regarding the legal status of hemp/CBD and marijuana for both animals and humans. For each statement in Table 10, there was a significant difference in stated level of agreement based on graduation year and their state's recreational marijuana laws, with the exception of hemp/CBD products for animals (only significantly different based on state's recreational marijuana laws and not graduation year) (Table 10).

TABLE 10

Table 10. Participants' views regarding legal status of hemp/CBD/marijuana in animals and humans.

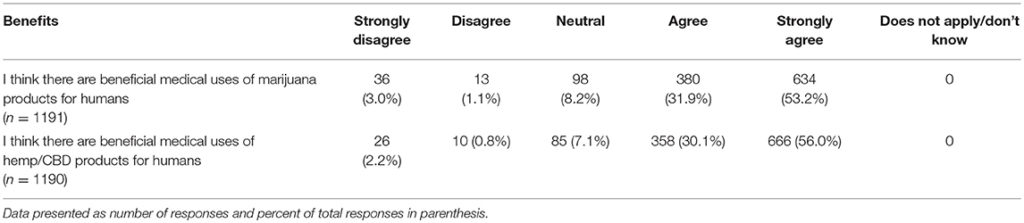

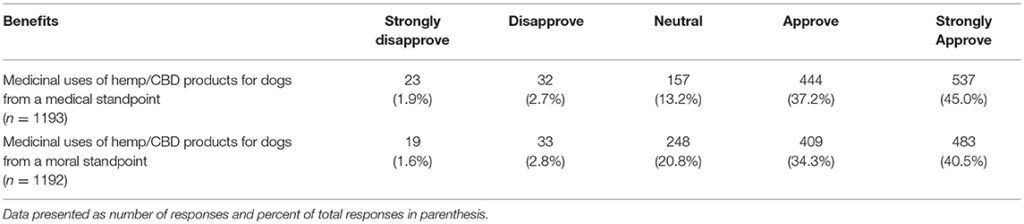

Lastly, participants were asked to report their views on the potential benefits of marijuana and CBD products for humans as well as their support in using CBD products for animals from both a medical and ethical viewpoint. Most participants agreed or strongly agreed that both marijuana and CBD products offer benefits for humans and expressed support for use of CBD products for animals. There was a significant difference based on graduation year, with more recent graduates reporting higher agreement levels for the question related to beneficial medical uses of marijuana products for humans (chi square 25.95, p = 0.039). This difference was not observed for the question on the beneficial medical uses of hemp/CBD products for humans. There were also no differences based on year of graduation or laws regarding recreational marijuana in participants' state of practice, for questions related to the benefits of marijuana or CBD/hemp products for animals (Tables 11, 12).

TABLE 11

Table 11. Participants' views regarding the potential medical benefits of hemp/CBD/marijuana for humans.

TABLE 12

Table 12. Participants' reported level of support regarding the potential medical benefits of hemp/CBD/marijuana for dogs.

Discussion

The current study investigated veterinarians' views and experiences surrounding CBD products for dogs. A recent national study assessing dog owners' views and behaviors surrounding CBD product usage for their dogs found that the most commonly reported use by owners of CBD products was for pain relief, followed by reduction of inflammation, and relief from anxiety (15). Pain relief was also the predominant use reported by owners in a 2016 study (16). Significant side effects were reported by <5% of owners, with most participants reported not observing any side effects (15). The significant side effect observed most frequently was lethargy yet even this effect was reported by only 3.9% of owners.

These findings assessing owners' experiences were validated in the current study. When veterinarians were asked what specific conditions or diseases clients enquired about treating with CBD products, the most common responses were pain management, anxiety and seizures. These were also the top three topics listed by veterinarians when asked for conditions about which they initiated CBD conversations with their clients.

When asked about potential benefits of CBD products for a variety of conditions, veterinarians reported observing (either first-hand or through owner reports) that CBD was the most helpful for chronic pain (reported as very helpful by 34% and somewhat helpful by 56% of veterinarians) followed by acute pain (very helpful, 23% and somewhat helpful by 60% of veterinarians). CBD was also deemed to be helpful for reducing anxiety and seizure frequency/severity by over 75% of participants. The recent clinical trials on CBD for seizures (13) and pain management (14) support these veterinarians' reported experiences.

A variety of CBD products are currently available for purchase and participants reported the most familiarity with biscuits/edibles, yet even for these, approximately 40% of veterinarians reported having no experience. Interestingly, when owners were asked what form of CBD they gave to their pets, the most common response was capsules/pills and biscuits/edibles were a distant second (56.9% compared to 29.3%)

In general, veterinarians appear reticent to initiate conversations with clients about CBD, with 85% reporting they rarely or never initiated such conversations. Few reported advising clients about CBD (73% either never or rarely), and even fewer recommended (83% either never or rarely) or prescribed (91% either never or rarely) CBD products. The most common reason given for not advising about or recommending CBD was not feeling knowledgeable enough. When asked why they did not prescribe CBD products, the most common response was the fact that it is illegal. It is interesting to note that participants who work in states that have legalized recreational marijuana are more likely to advise about and recommend CBD products, but even they do not prescribe. More experienced veterinarians were more likely to recommend and prescribe, but not to advise clients about CBD products. Yet, even with these differences, most veterinarians in the current study, do not advise about, recommend or prescribe CBD products.

Given the dearth of information available about CBD products, it is not surprising that veterinarians do not feel knowledgeable about the topic. To this point, a significant number of participants reported not knowing much or anything about the therapeutic (47%) or toxic (62%) effects of CBD products. It is also clear that the participating veterinarians do not feel they are obtaining the information they need from their state veterinary organizations or state veterinary boards. When asked, <25% of respondents feel these entities provide sufficient guidance for them to practice within the state or federal law. Unfortunately, this lack of knowledge, and therefore veterinarians' confidence to initiate CBD related conversations with their clients leaves pet owners with limited options to obtain reliable information. It is alarming, but not surprising, that CBD company websites are the source most consulted by pet owners for CBD information (16). This does not appear to be due to owners' comfort levels; over 83% of surveyed owners reported feeling comfortable talking to their vet about CBD (15). Yet, results from this current study show that only 45% of veterinarians feel comfortable talking to clients about CBD. Even more telling, only 62% of surveyed veterinarians feel comfortable talking to other veterinarians about the topic.

Veterinarians in the current sample overwhelmingly support further research into both the therapeutic use and toxicity of CBD as well as the toxicity of marijuana. The majority do not feel that CBD or marijuana should remain defined as Schedule I drugs by the DEA, nor feel that these substances should remain illegal for use in animals or humans. Taken together, these responses suggest that the veterinary community is receptive to exploring the potential of cannabis products and hungers for scientific data and clinical trials. These results are similar to those of a recent study exploring attitudes toward marijuana among medical students attending an allopathic medical school in Colorado. These students supported marijuana legal reform (reclassifying marijuana so that it is no longer a Schedule 1 substance), increased research, and medicinal uses of marijuana, but voiced concerns about potential risks and therefore, many expressed reluctance about recommending marijuana to patients (17). Another study of health care providers working in Washington, USA had similar results whereby they reported the need for additional training and education; and given their current knowledge level, did not feel comfortable recommending medical cannabis (18). New York physicians (19) as well as a national sample of oncologists (20) share similar sentiments. In fact, these challenges are faced by physicians worldwide (21–23). A limitation of this study is that only veterinarians who subscribe to VIN (Veterinary Information Network) participated in this study. Although VIN has a large member base, it does not represent all veterinarians. It is possible that members of VIN may have different views on this topic than all veterinarians; therefore, we must be cautious to not extrapolate these results to the entire profession. Nevertheless, the authors believe the results are informative on this timely topic and the conclusion that more research is needed on the potential benefits and potential toxicities of CBD products can be generalized to the profession outside of VIN. The authors believe that VIN membership is reflective of the overall population of veterinarians in the U.S. VIN consists of 34, 917 members located in all 50 states. The average age of VIN members is 45.5 years compared to the average age of veterinarians in the U.S. of 44.1 years. Women constitute 69% of VIN members and 65% of U.S. veterinarians.

The sales of natural pet supplements nearly doubled between 2008 and 2014 with no signs of slowing down; U.S. retail sales are projected to grow 3–5% annually (25). The use of CBD products for animals is expected to increase as pet owners look for alternative ways to care for their pets. And while pet treats and food are regulated, pet supplements fall in a gray unregulated zone because they are not classified as drugs or food. Given the constantly changing laws and regulations on cannabis products as well as the lack of scientific study, obtaining accurate information on cannabis products is critically important. Certainly, current laws and political forces make it challenging for veterinarians to gain the information they need to feel confident discussing CBD with their clients and offering sound advice, yet it is imperative for the veterinary field to rise to this challenge. Given the positive feelings expressed by veterinarians in this study, it is suggested that all those affected by both the potential benefits as well as the risks, work together for legislative change that would allow for the expansion of knowledge needed to best capitalize on this potential medical tool for companion animals.

RESEARCH

Pharmacokinetics, Safety, and Clinical Efficacy of Cannabidiol Treatment in Osteoarthritic Dogs

Lauri-Jo Gamble1, Jordyn M. Boesch1, Christopher W. Frye1, Wayne S. Schwark2, Sabine Mann3, Lisa Wolfe4, Holly Brown5, Erin S. Berthelsen1 and Joseph J. Wakshlag1*

Objectives: The objectives of this study were to determine basic oral pharmacokinetics, and assess safety and analgesic efficacy of a cannabidiol (CBD) based oil in dogs with osteoarthritis (OA).

Methods: Single-dose pharmacokinetics was performed using two different doses of CBD enriched (2 and 8 mg/kg) oil. Thereafter, a randomized placebo-controlled, veterinarian, and owner blinded, cross-over study was conducted. Dogs received each of two treatments: CBD oil (2 mg/kg) or placebo oil every 12 h. Each treatment lasted for 4 weeks with a 2-week washout period. Baseline veterinary assessment and owner questionnaires were completed before initiating each treatment and at weeks 2 and 4. Hematology, serum chemistry and physical examinations were performed at each visit. A mixed model analysis, analyzing the change from enrollment baseline for all other time points was utilized for all variables of interest, with a p ≤ 0.05 defined as significant.

Results: Pharmacokinetics revealed an elimination half-life of 4.2 h at both doses and no observable side effects. Clinically, canine brief pain inventory and Hudson activity scores showed a significant decrease in pain and increase in activity (p < 0.01) with CBD oil. Veterinary assessment showed decreased pain during CBD treatment (p < 0.02). No side effects were reported by owners, however, serum chemistry showed an increase in alkaline phosphatase during CBD treatment (p < 0.01).

Clinical significance: This pharmacokinetic and clinical study suggests that 2 mg/kg of CBD twice daily can help increase comfort and activity in dogs with OA.

Introduction

Routine nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) treatments, though efficacious, may not provide adequate relief of pain due to osteoarthritis (OA) and might have potential side effects that preclude its use, particularly in geriatric patients with certain comorbidities, such as kidney or gastrointestinal pathologies (1–4). In a systematic review of 35 canine models of OA and 29 clinical trials in dogs, treatment with NSAIDs caused adverse effects in 35 of the 64 (55%) studies, most commonly being gastro-intestinal signs (3). Although other pharmacological agents are advocated, such as gabapentin or amantadine, there is little evidence regarding their efficacy in dogs with chronic or neuropathic pain related to OA. Recent medical interest in alternative therapies and modalities for pain relief has led many pet owners to seek hemp related products rich in cannabinoids.

The endocannabinoid receptor system is known to play a role in pain modulation and attenuation of inflammation (5–7). Cannabinoid receptors (CB1 and CB2) are widely distributed throughout the central and peripheral nervous system (8–10) and are also present in the synovium (11). However, the psychotropic effects of certain cannabinoids prevent extensive research into their use as single agents for pain relief (5, 12). The cannabinoids are a group of as many as 60 different compounds that may or may not act at CB receptors. One class of cannabinoids, cannabidiol (CBD), may actually be an allosteric non-competitive antagonist of CB receptors (13). In lower vertebrates, CBD is also reported to have immunomodulatory (14), anti-hyperalgesic (15, 16), antinociceptive (17, 18), and anti-inflammatory actions (5, 19), making it an attractive therapeutic option in dogs with OA. Currently there are several companies distributing nutraceutical derivatives of industrial hemp, rich in cannabinoids for pets, yet little scientific evidence regarding safe and effective oral dosing exists.

The objectives of this study were to determine: (1) single-dose oral pharmacokinetics, (2) short-term safety, and (3) efficacy of this novel CBD-rich extract, as compared to placebo, in alleviating pain in dogs with OA. Our underlying hypotheses were that appropriate dosing of CBD-rich oil would safely diminish perceived pain and increase activity in dogs with OA.

Materials and Methods

CBD Oil and Protocols Approval

The industrial hemp used in this study was a proprietary hemp strain utilizing ethanol and heat extraction with the final desiccated product reconstituted into an olive oil base containing ~10 mg/mL of CBD as an equal mix of CBD and carboxylic acid of CBD (CBDa), 0.24 mg/mL tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), 0.27 mg/mL cannabichromene (CBC), and 0.11 mg/mL cannabigerol (CBG); all other cannabinoids were less than 0.01 mg/mL. Analysis of five different production runs using a commercial analytical laboratory (MCR Laboratories, Framingham, MA) show less than a 9% difference across batches for each of the detected cannabinoids listed above. The study was performed after the Cornell University institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) approved the study following the guidelines for animal use according to the IACUC. Client owned dogs were enrolled after informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Pharmacokinetics

An initial investigation into single-dose oral pharmacokinetics was performed with 4 beagles (3.5–7 years, male castrated, 10.7–11.9 kg). Each dog received a 2 mg/kg and an 8 mg/kg oral dosage of CBD oil, with a 2-week washout period between each experiment. The dogs were fed 2 h after dosing. Physical examination was performed at 0, 4, 8, and 24 h after dosing. Attitude, behavior, proprioception, and gait were subjectively evaluated at each time point during free running/walking and navigation around standard traffic cones (weaving). Five milliliters of blood was collected at time 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h after oil administration. Blood samples were obtained via jugular venipuncture and transferred to a coagulation tube for 20 min. Samples were centrifuged with a clinical centrifuge at 3,600 × g for 10 min; serum was removed and stored at −80°C until analysis using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) at Colorado State University Core Mass Spectrometry facility.

Extraction of CBD from Canine Serum and Mass Spectrometry Analysis

CBD was extracted from canine serum using a combination of protein precipitation and liquid-liquid extraction using n-hexane as previously described (20), with minor modifications for microflow ultra-high pressure liquid chromatography (UHPLC). Briefly, 0.05 mL of canine serum was subjected to protein precipitation in the presence of ice-cold acetonitrile (80% final concentration), spiked with deuterated CBD as the internal standard (0.06 mg/mL, CDB-d3 Cerilliant, Round Rock, TX, USA). 0.2 mL of water was added to each sample prior to the addition of 1.0 mL of hexane to enhance liquid-liquid phase separation. Hexane extract was removed and concentrated to dryness under laboratory nitrogen. Prior to LC-MS analysis, samples were resuspended in 0.06 mL of 100% acetonitrile. A standard curve using the CBD analytical standard was prepared in canine serum non-exposed to CBD and extracted as above. Cannabidiol concentration in serum was quantified using a chromatographically coupled triple-quadropole mass spectrometer (UHPLC-QQQ-MS) using similar methods as previously described (21).

CDB Serum Concentration Data Analysis

From the UHPLC-QQQ-MS data, peak areas were extracted for CBD detected in biological samples and normalized to the peak area of the internal standard CBD-d3, in each sample using Skyline (22) as well as an in-house R Script (www.r-project.org). CBD concentrations were calculated to nanograms per mL of serum as determined by the line of regression of the standard curve (r2 = 0.9994, 0–1,000 ng/mL). For this assay, the limits of detection (LOD) and limits of quantification (LOQ) represent the lower limits of detection and quantification for each compound in the matrix of this study (23, 24). Pharmacokinetic variables were estimated by means of non-compartmental analysis, utilizing a pharmacokinetic software package (PK Solution, version 2.0, Montrose, CO, USA).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for the Clinical Trial

The study population consisted of client-owned dogs presenting to Cornell University Hospital for Animals for evaluation and treatment of a lameness due to OA. Dogs were considered for inclusion in the study if they had radiographic evidence of OA, signs of pain according to assessment by their owners, detectable lameness on visual gait assessment and painful joint(s) on palpation. Each dog had an initial complete blood count ([CBC] Bayer Advia 120, Siemens Corp., New York, NY, USA) and serum chemistry analysis (Hitachi 911, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) performed to rule out any underlying disease that might preclude enrolment. Elevations in alkaline phosphatase (ALP), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were allowed if prior hepatic ultrasound was deemed within normal limits except for potential non-progressive nodules (possible hepatic nodular hyperplasia). All owners completed a brief questionnaire to define the affected limb(s), duration of lameness, and duration of analgesic or other medications taken. All dogs underwent radiographic examination of affected joints and a radiologist confirmed the presence or absence of OA, and excluded the presence of concomitant disease that might preclude them from enrolment (i.e., lytic lesions).

During the trial, dogs were only allowed to receive NSAIDs, fish oil, and/or glucosamine/chondroitin sulfate without any change in these medications for 4 weeks prior to or during the 10-week study period as standard of care for the disease process. Other analgesic medications used, such as gabapentin and tramadol, were discontinued at least 2 weeks prior to enrolment. Dogs were excluded if they had evidence of renal, uncontrolled endocrine, neurologic, or neoplastic disease, or were undergoing physical therapy. Every dog was fed its regular diet with no change allowed during the trial.

Clinical Trial

The study was a randomized, placebo-controlled, owner and veterinarian double-blind, cross-over trial. Dogs received each of two treatments in random order (Randomizer iPhone Application): CBD, 2 mg/kg every 12 h, or placebo (an equivalent volume of olive oil with 10 parts per thousands of anise oil and 5 parts per thousands of peppermint oil to provide a similar herbal smell) every 12 h. Each treatment was administered for 4 weeks with a 2-week washout period in between treatments. Blood was collected to repeat complete blood counts and chemistry analysis at weeks 2 and 4 for each treatment.

At each visit, each dog was evaluated by a veterinarian based on a scoring system previously reported (25) as well as by its owner (canine brief pain inventory [CBPI], Hudson activity scale) before treatment initiation and at weeks 2 and 4 thereafter (26–28).

Statistical Analysis

Initial power analysis was performed to assess number of dogs needed for this study as a cross over design with a power set 0.80 and alpha of 0.05 using prior data suggesting a baseline CBPI or Hudson score change of ~15 points (two tailed) with a standard deviation of 20. When calculated it was assumed that 14 dogs would be necessary to find differences in outcomes of interest (29).

Statistical analysis was performed with a commercially available software package (JMP 12.0, Cary, NC, USA). All continuous data were assessed utilizing a Shapiro–Wilk test for normality. Considering a majority of our blood, serum and scoring data were normally distributed a mixed model analysis was used to analyze these outcomes, including the fixed effects of treatment, time, sequence of treatment assignment, gender, age, NSAID usage, treatment × time; as well as random effects of observation period, period nested within dog, time point nested within period nested within dog to account for the hierarchical nature of data in a cross-over design as well as repeated measurements for each dog. For ordinal veterinary scoring data a similar linear mixed model was used, but differences from baseline were first calculated to approximate a normal distribution to meet assumptions for a mixed model analysis. Residual diagnostics of all final models showed that residuals were normally distributed and fulfilled the assumption of homoscedasticity, and assumptions where therefore met. This statistical modeling approach allowed for adequate control of hierarchical data structure necessary in a cross-over design, as well as for the performance of easily interpretable time × treatment Tukey post-hoc comparisons that were our main interest, as compared to an ordinal logistical regression (30, 31). To control for baseline differences and therefore the possible difference in relative change in CBPI pain, and activity interference assessments and Hudson scoring across dogs, the initial CPBI or Hudson Scores were included for these analyses as a covariate. Pairwise comparisons between all-time points of both groups were corrected for multiple comparisons with Tukey's post-hoc tests to examine the interaction of time and treatment variables, and to assess differences between change from baseline at any time point as they related to treatment. A p-value of less than 0.05 was defined as the significance cut-off.

Results

Pharmacokinetics

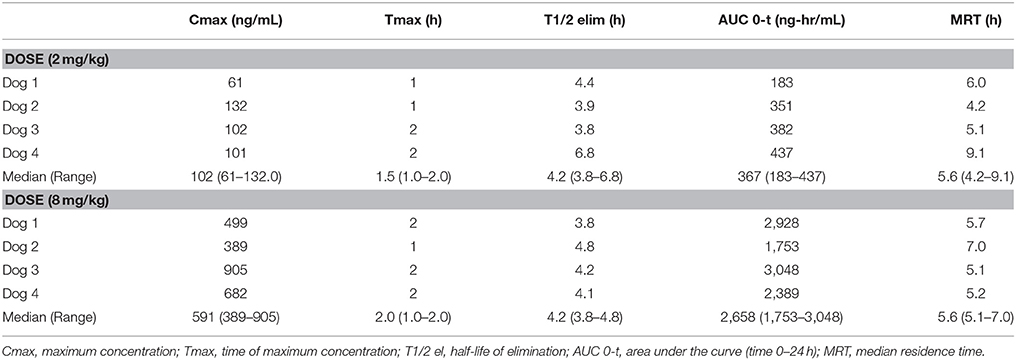

Pharmacokinetics demonstrated that CBD half-life of elimination median was 4.2 h (3.8–6.8 h) for the 2 mg/kg dose, and 4.2 h (3.8–4.8 h) for the 8 mg/kg dose (Table 1). Median maximal concentration of CBD oil was 102.3 ng/mL (60.7–132.0 ng/mL; 180 nM) and 590.8 ng/mL (389.5–904.5 ng/mL; 1.2 uM) and was reached after 1.5 and 2 h, respectively, for 2 and 8 mg/kg doses. No obvious psychoactive properties were observed on evaluation at any time point during the 2 and 8 mg/kg doses over 24 h. These results led to dosing during the clinical trial at 2 mg/kg body weight every 12 h, due the cost prohibitive nature of 8 mg/kg dosing for most larger patients, the impractical nature of more frequent dosing, the volume of oil necessary and anecdotal reports surrounding 0.5-2 mg/kg dosing recommended by other vendors.

TABLE 1

Table 1. Serum pharmacokinetic of single oral dosing (2 mg and 8 mg/kg) of CBD oil in dogs.

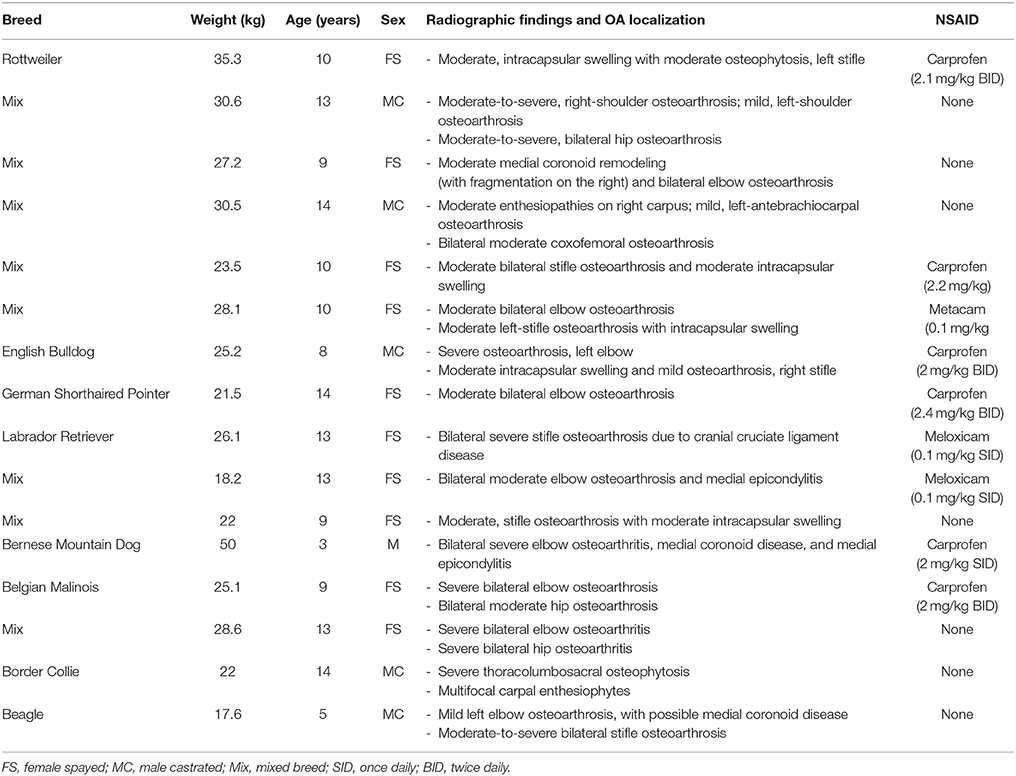

Dogs Included in the Clinical Trial

Twenty-two client-owned dogs with clinically and radiographically confirmed evidence of osteoarthritis were recruited. Sixteen of these dogs completed the trial and were included in the analyses; their breed, weight, age, sex, worse affected limb, radiographic findings, use of NSAIDs and sequence of treatments are summarized in Table 2. Dogs were removed due to osteosarcoma at the time of enrolment, gastric torsion (placebo oil), prior aggression issues (CBD oil), pyelonephritis/kidney insufficiency (CBD oil), recurrent pododermatitis (placebo oil), and diarrhea (placebo oil).

TABLE 2

Table 2. Characteristics of dogs enrolled in a placebo-controlled study investigating the effects of CBD on osteoarthritis.

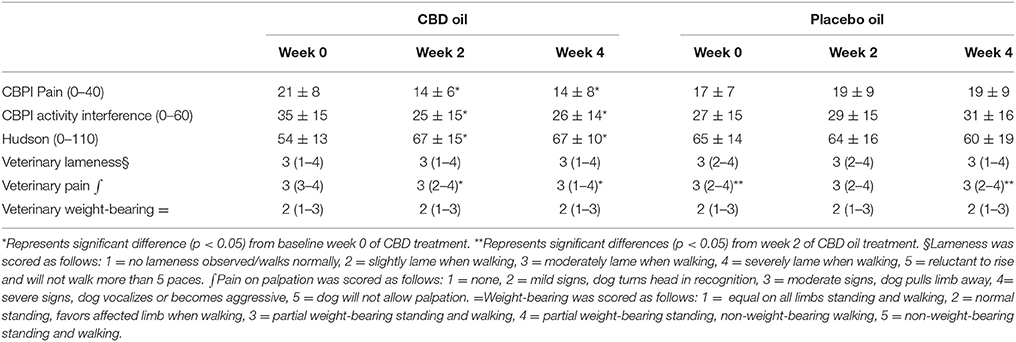

Clinical Trial

CBPI and Hudson change from baseline scores showed a significant decrease in pain and increase in activity (p < 0.01) at week 2 and 4 during CBD treatment when compared to baseline week 0, while no other statistical significances were observed across treatment in this cross-over design (Table 3). Lameness as assessed by veterinarians showed an increase from baseline in lameness with age (p < 0.01), whereas NSAID use (p = 0.03) reduced lameness scores. Veterinary pain scores showed a decrease from baseline in dogs on NSAIDs (p < 0.01). CBD oil resulted in a decrease in pain scores when compared to baseline on evaluation at both week 2 and week 4 (p < 0.01 and p = 0.02, respectively), and week 2 CBD oil treatment was lower than baseline placebo treatment (p = 0.02) and week 4 placebo treatment (p = 0.02). No other veterinary pain comparisons were statistically significant. No changes were observed in weight-bearing capacity when evaluated utilizing the veterinary lameness and pain scoring system (Table 3).

TABLE 3

Table 3. Canine Brief Pain Inventory (Pain and Activity questions) and Hudson Scale mean and standard deviation; lameness, weight-bearing and pain scores median and ranges at each time for cannabidiol (CBD) and placebo oils.

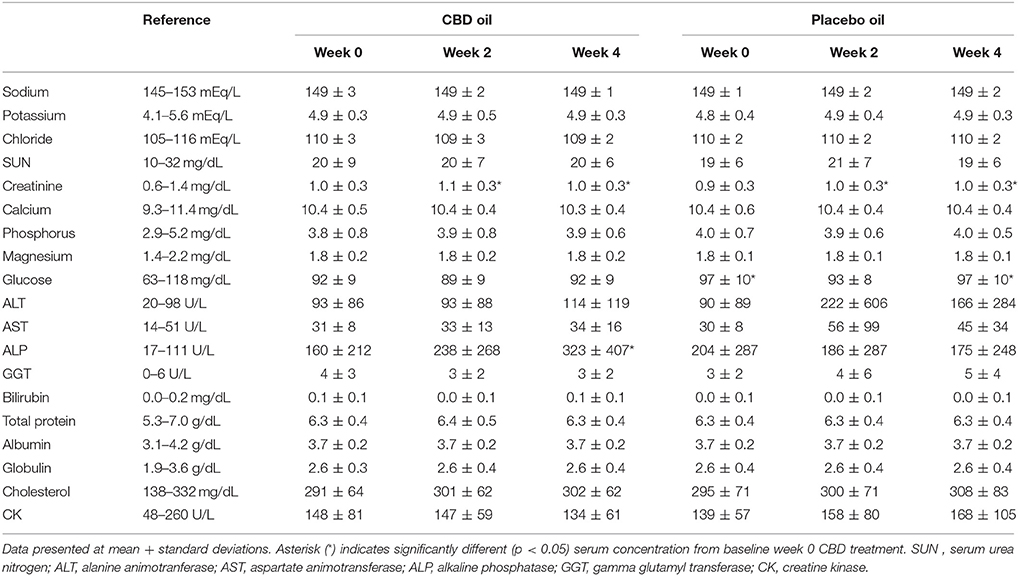

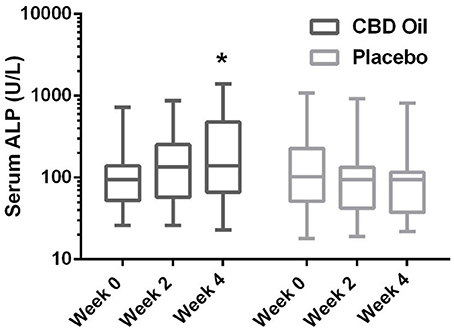

Chemistry analysis and CBC were performed at each visit. No significant change in the measured CBC values was noted in either the CBD oil or placebo treated dogs (data not shown). Serum chemistry values were not different between placebo compared to CBD oil (Table 4), except for alkaline phosphatase (ALP) which significantly increased over time from baseline by week 4 of CBD oil treatment (p < 0.01); with nine of the 16 dogs showing increases over time (Figure 1). Glucose was increased in dogs receiving the placebo oil at each time point (p = 0.04) and creatinine levels increased over time in both dogs receiving CBD oil and those receiving placebo oil (p < 0.01); though all values remained within reference ranges. Other notable significances in serum chemistry values were associated with primarily age or NSAID use. An increase in age was associated with significantly higher blood urea nitrogen (BUN; p < 0.01), calcium (p = 0.01), phosphorus (p < 0.01), alanine aminotransferase (ALT; p = 0.03), alkaline phosphatase (ALP; p = 0.01), gamma glutamyltransferase (GGT; p = 0.02), globulin (p = 0.02), and cholesterol (p < 0.01) values. NSAID use was associated with significantly higher BUN (p = 0.003), and creatinine (p = 0.017), and significant decreases in total protein (p < 0.001) and serum globulin (p < 0.001).

TABLE 4

Table 4. Serum chemistry values of dogs receiving CBD or placebo oils.

FIGURE 1

Figure 1. Box-and-whisker plot of serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity at each time for treatment and placebo oils. Box represents the mean and 25th and 75th percentile and the whiskers represent the 99th and 1st percentiles. *Indicates a significant difference (p < 0.05) from week 0 CBD treatment.

Discussion

To date, an objective evaluation of the pharmacokinetics of a commercially available industrial hemp product after oral dosing in dogs is absent. This study showed that the terminal half-life of oral CBD, as the most abundant cannabinoid in this specific preparation when in an oil base, was between 4 and 5 h, suggesting it was bioavailable with a dosing schedule of 2 mg/kg at least twice daily. This half-life was shorter than a previous report after intravenous (1.88–2.81 and 3.75–5.63 mg/kg) and oral (7.5–11.25 mg/kg) administration (32). In the intravenous study, CBD distribution was rapid, followed by prolonged elimination with a terminal half-life of 9 h. When examining prior oral CBD bioavailability it was determined to be low and highly variable (0–19% of dose) with three dogs showing no absorption. This may be due to the first pass effect in the liver, and the product was not in an oil base, but a powder within a gelatin capsule being a different delivery vehicle (32). After initially seeing no neurological effects at the 2 mg/kg dose a 8 mg/kg dose was chosen to assess the potential neurological effects since mistaken overdosing can occur clinically, and a higher dose might have been necessary since the prior study showed poor absorption. Although our dogs were fasted the delivery vehicle was olive oil which is a food item. The absorption may be greater and more consistent because of the oil-based vehicle which may be due to the lipophilic nature of CBD, hence delivery with food may be preferable (32, 33). As previously demonstrated, CBD biotransformation in dogs involves hydroxylation, carboxylation and conjugation, leading to relatively rapid elimination suggesting a more frequent dosing schedule (34). The dosing schedule of twice per day was chosen due to the practical nature of this dosing regimen even though the elimination is well within a three or four time a day dosing regimen. Our hope was that the lipophilic nature of CBD would allow for a steady state over time, and future studies examining 24 h pharmacokinetics with different dosing regimens with larger numbers of dogs, and steady state serum pharmacokinetics after extended treatment in a clinical population are sorely needed.

The main objective of this study was to perform an owner and veterinary double-blinded, placebo-controlled, cross-over study to determine the efficacy of CBD oil in dogs affected by OA. Despite our small sample size, short study duration and heterogeneity of OA signs, CBPI and Hudson scores showed that CBD oil increase comfort and activity in the home environment for dogs with OA. Additionally, veterinary assessments of pain were also favorable. Although a caregiver placebo effect should be considered with subjective evaluations by owners and veterinarians (35), the cross-over design limits confounding covariates since each dog serves as its own control. Our statistical model controlled for the possible effect of treatment sequence. The lack of a placebo effect in our study may be due to nine of the 16 owners being intimately involved in veterinary medical care, all of whom have an understanding of the placebo effect making them more cognizant of improvements when providing feedback. In addition, there was a noticeable decrease in Hudson scores and rise in CBPI scores during the initiation placebo treatment suggesting a potential carry over effect of CBD treatment indicating that a longer washout period might be indicated in future studies. This carry over effect may have resulted in some improved perceptions at the initiation of the placebo treatment which were eliminated by week 4 of placebo treatment, underscoring the importance of longer term steady state PK studies in dogs.

There was no significant difference in subjective veterinary lameness score and weight-bearing capacity throughout the study. Kinetic data was obtained from these dogs (data not shown), however 11 of the 16 dogs had significant bilateral disease (stifle, coxofemoral, or elbow) making evaluation of peak vertical force or symmetry tenuous at best. Unilateral disease in any of the aforementioned joints would be ideal to study the kinetic effects of this or similar extracts for pain relief leading to better objective outcomes. The population we used in our investigation was representative of dogs presenting in a clinical setting for management of OA and represents the typical OA patient.

Currently, NSAIDs are the primary treatment for OA and are associated with negative effects on the gastrointestinal tract and glomerular filtration (2). In the current study, no significant difference was noted in BUN, creatinine, or phosphorus between dogs treated with the CBD oil vs. the placebo oil, while NSAID treatment resulted in a higher creatinine concentration. A mild rise in creatinine from baseline was noted in both groups at weeks 2 and 4, the hydration status of the dogs was unknown; however changes in albumin sodium, and chloride were unchanged suggesting euhydration, and all creatinine values remained within the reference interval. Increased ALP activity is fairly sensitive for hepatobiliary changes in this age group, but not specific. Increased ALP activity noted in nine dogs in the CBD treatment group may be an effect of the hemp extract attributed to the induction of cytochrome p450 mediated oxidative metabolism of the liver (reported previously with prolonged exposure to cannabis) (36–38). Other causes of cholestasis, increased endogenous corticosteroid release from stress, or a progression of regenerative nodular hyperplasia of the liver cannot be ruled out. Without concurrent significant rise in ALT in the CBD treatment to support hepatocellular damage, or biopsy for further clarification, the significance is uncertain. As such, it may be prudent to monitor liver enzyme values (especially ALP) while dogs are receiving industrial hemp products until controlled long term safety studies are published.

A recent survey reported that pet owners endorse hemp based treats and products because of perceived improvement in numerous ailments, as hemp products were moderately to very helpful medicinally (39). Some of the conditions thought to be relieved by hemp consumption were: pain, inflammation, anxiety and phobia, digestive system issue, and pruritus (39). One immunohistochemical study suggested that cannabinoids could protect against the effects of immune-mediated and inflammatory allergic disorders in dogs (40) whereas another uncontrolled study suggested that CBD has anticonvulsant and anti-epileptic properties in dogs (41). The apparent analgesic effect of the industrial hemp based oil observed in the present study may be attributable to downregulation of cylooxygenase enzymes, glycine interneuron potentiation, transient receptor potential cation receptor subfamily V1 receptor agonism (peripheral nerves), and/or g-protein receptor 55 activation (immune cells), influencing nociceptive signaling and/or inflammation (14, 42, 43).

The industrial hemp product used in this study is a proprietary strain-specific extract of the cannabinoids outlined in the methods with relatively high concentrations of CBD and lesser quantities of other cannabinoids as well as small amounts of terpenes that may have synergistic effects often termed the “entourage effect.” This brings to light that fact that different strains of cannabis produce differing amounts of CBD and other related cannabinoids making the results of this study specific to this industrial hemp extract that may not translate to other available products due to differing cannabinoid concentrations in this largely unregulated market.

In conclusion, this particular product was shown to be bioavailable across the small number of dogs examined in the PK portion of the study, and dogs with OA receiving this industrial hemp extract high in CBD (2 mg/kg of CBD) were perceived to be more comfortable and active. There appear to be no observed side effects of the treatment in either the dogs utilized in the PK study at 2 and 8 mg/kg, or dogs undergoing OA treatment for a month duration. There were some dogs with incidental rises in alkaline phosphatase that could be related to the treatment. Further long-term studies with larger populations are needed to identify long-term effects of CBD rich industrial hemp treatment, however short term effects appear to be positive.

RESEARCH

Cannabinoid receptor type 1 and 2 expression in the skin of healthy dogs and dogs with atopic dermatitis.

Campora L1, Miragliotta V, Ricci E, Cristino L, Di Marzo V, Albanese F, Federica Della Valle M, Abramo F.

Author information

Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To determine the distribution of cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1) and cannabinoid receptor type 2 (CB2) in skin (including hair follicles and sweat and sebaceous glands) of clinically normal dogs and dogs with atopic dermatitis (AD) and to compare results with those for positive control samples for CB1 (hippocampus) and CB2 (lymph nodes).

SAMPLE:

Skin samples from 5 healthy dogs and 5 dogs with AD and popliteal lymph node and hippocampus samples from 5 cadavers of dogs.

PROCEDURES:

CB1 and CB2 were immunohistochemically localized in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections of tissue samples.

RESULTS:

In skin samples of healthy dogs, CB1 and CB2 immunoreactivity was detected in various types of cells in the epidermis and in cells in the dermis, including perivascular cells with mast cell morphology, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells. In skin samples of dogs with AD, CB1 and CB2 immunoreactivity was stronger than it was in skin samples of healthy dogs. In positive control tissue samples, CB1 immunoreactivity was detected in all areas of the hippocampus, and CB2 immunoreactivity was detected in B-cell zones of lymphoid follicles.

CONCLUSIONS AND CLINICAL RELEVANCE:

The endocannabinoid system and cannabimimetic compounds protect against effects of allergic inflammatory disorders in various species of mammals. Results of the present study contributed to knowledge of the endocannabinoid system and indicated this system may be a target for treatment of immune-mediated and inflammatory disorders such as allergic skin diseases in dogs.

RESEARCH

Simple and Fast Gas-chromatography Mass Spectrometry Assay to Assess Delta 9-Tetrahydrocannabinol and Cannabidiol in Dogs Treated with Medical Cannabis for Canine Epilepsy

Metrics

To date, an increasing number of pet owners, especially in the USA, are using cannabis-derived products containing generally delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) to help their animals' health. Unfortunately, studies on the clinical use of cannabinoids in veterinary medicine are still limited, and the application of analytical methodologies for the determination of cannabinoids in animal (especially dog) biological matrices such as plasma, is still missing.

Methods

A reliable, fast, accurate, simple gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) method was developed and validated for the quantification of THC and CBD in plasma samples of eight dogs under therapeutic treatment for epilepsy and receiving oral administration of medical cannabis (Bediol).

Results

The method was linear for both the analytes under investigation with coefficients of determination (r2) of at least 0.99. Absolute analytical recovery (mean ± SD) ranged from 80.6 ± 6.2% for THC and 81.7 ± 4.3% for CBD. The matrix effect showed less than 10% analytical suppression due to endogenous substances for both the analytes. The intra-assay and inter-assay precision values ranged from 4.9% to 12.7%, and from 5.2% to 8.7% respectively. The intra-assay and inter-assay accuracy values ranged from 2.3% to 9.6% and from 3.4% to 13.0%, respectively.

Conclusion

The validated method was successfully applied to real samples; moreover, to assess the potential of the method applicability and robustness in future veterinary clinical studies on cannabinoids therapy, we attempted to follow the kinetic of THC and CBD in the plasma of two dogs under therapy at different times after Bediol administration.

Source:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6338022/